Read our most popular nursing stories

- Interprofessional collaboration is the practice of approaching patient care from a team-based perspective, with a team comprised of multiple health workers with varying professional backgrounds. By implementing interprofessional collaboration into healthcare environments, multiple disciplines can work more effectively as a team to help improve patient outcomes and better the workplace.2023-09-11T04:00:00Z

- Through the Nurse Innovation Fellowship Program by Johnson & Johnson, powered by Penn Nursing and the Wharton School, nursing leaders are immersed in the innovation process to redefine the future of patient care and professional well-being by tackling a real problem at their health systems.2024-07-12T17:10:35.302Z

- In the last two years, the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act has created programs that increase access to, and reduce stigma of, evidence-based mental health treatment for nurses and all healthcare workers. But there is much more work to be done to support our nation’s healthcare workforce. As Congress looks to reauthorize the bill, here are three areas of focus for 2024 and beyond.2024-03-13T17:31:28.448Z

- Through an action network created by the Institute of Healthcare Improvement and Johnson & Johnson Foundation, with the support of the American Organization for Nursing Leadership, five nurse-led teams piloted acute care delivery solutions to support and empower a thriving nursing workforce. Across three phases and 22 months, here’s what they found – and how health systems nationwide can implement their learnings.2024-08-09T14:44:26.583Z

- The Johnson & Johnson Nurse Innovation Fellowship, powered by Penn Nursing and the Wharton School, is built on the concept of applying design thinking and human-centered design to real-world challenges within health systems. But what is design thinking? And how does this concept help nurses enhance their innovative skills and drive change?2024-01-19T15:19:01.445Z

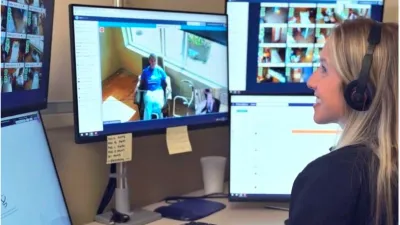

- Data and information gathering is vital to healthcare outcomes and quality – from identifying best practices for taking care of patients to predicting and planning resource needs and staying nimble during constant change. The role of nurses in technology and informatics is more critical than ever as AI is poised to streamline systems and practices.2021-10-22T20:34:36.255Z

- Ten nurse-led multidisciplinary health system teams from around the world were selected as finalists for the NurseHack4Health Pitch-A-Thon, with the chance to be awarded up to $150,000 in grant funding to bring solutions for a thriving workforce and healthy work environment to life. Meet the finalist teams below!2024-10-04T15:37:33.603Z

- A new resource from the Duke University School of Nursing is empowering nurses to make artificial intelligence (AI) an ally in their nursing practice. Nurse and Associate Professor Michael Cary, PhD, RN, FAAN emphasizes the importance of training and educating nurses for practice in the era of AI and how to use it to best benefit patients.2024-09-09T16:08:19.053Z

- When Hiyam Nadel, RN, MBA, CGC, gives lectures to nurses, she often begins by showing a roll of tape and asking a simple question: “How many things have you done with a piece of tape - making modifications to equipment that wasn’t working quite right?”2018-10-08T18:50:55.193Z

- Throughout history, nurses have played an outsized role in interacting with patients, with critical roles in prevention, education, treatment and recovery. In celebration of International Women's Day and Women’s History Month, meet nurses whose innovative approaches to patient care have profoundly changed human health.2020-03-17T19:34:15.339Z

- Cardiac care nurse Michele Santoro and her fellow clinicians at the Yale New Haven Heart and Vascular Center routinely race against time to save lives. In honor of American Heart Month, read on to find out how her innovations combine technology and a human touch to transform cardiovascular care delivery and improve patient outcomes.2024-02-20T16:29:31.234Z